By Maggie BenZvi at Coffee or Die Magazine

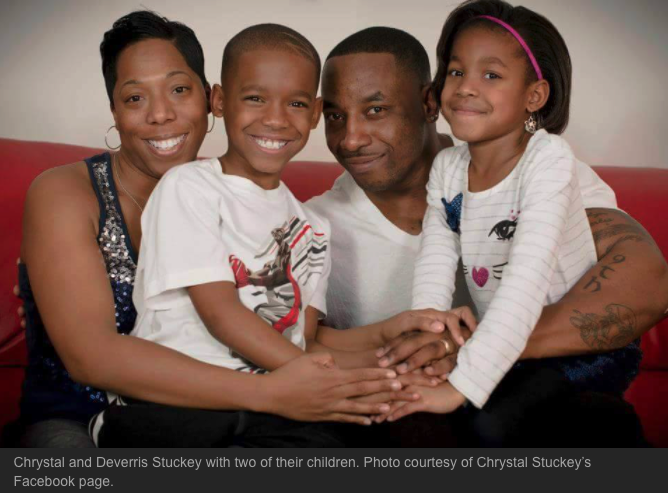

When Chrystal Stuckey got a terrible headache on Christmas Day in 2015, she went to the doctor. A master sergeant in the 96th Force Support Squadron, stationed at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, she took her health very seriously for the sake of her four children.

But the doctors on base were no help, and her headaches steadily got worse. They suggested she adjust her diet, but it made no difference. They diagnosed her with offset vertigo and she began to take medication — to no avail. After a year of increasing pain, she was finally given a referral to a hospital that was hours away in Birmingham, Alabama. She went to Birmingham and found that her doctors had sent the wrong paperwork. She couldn’t be seen.

Stuckey was eventually diagnosed with hydrocephalus, but treatment was slow in coming. Her husband, Deverris, who was also in the Air Force, was stationed in Korea at the time, and every phone call was heartbreaking.

“I think it was like two or three days before her death, and she said, ‘It feels like my head is going to burst open. Like my head is going to explode from this pressure. I can’t take it.’ And no one — no one did nothing,” he told Coffee or Die Magazine.

Stuckey died while her mother frantically drove her back toward Birmingham with her two oldest children in the backseat. They made it as far as a small town in Alabama called Georgiana.

“She was asleep,” Deverris said, “and when she woke up she said it felt like somebody was stabbing her in the head.” Stuckey took off her wedding ring, handed it to her mother, and told her mother she knew she was dying. Then she lost consciousness. She was brain-dead before a helicopter could transport her to the hospital in Birmingham. Doctors there told her husband that if she had been there 45 minutes earlier, she could have been saved.

The Stuckey family is one of 278, as of May, who have filed claims of medical malpractice with the Department of Defense under the provision of the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act known as the Richard Stayskal Military Medical Accountability Act.

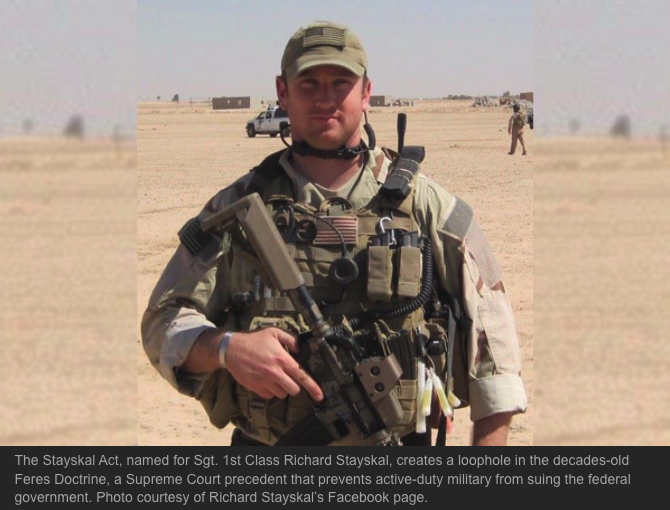

Named after a Green Beret who lobbied tirelessly after his lung cancer diagnosis, the Stayskal Act creates a loophole in the decades-old Feres Doctrine, a Supreme Court precedent that prevents active-duty military from suing the federal government. After more than a year of delays, the Department of Defense finally released its interim rule for the new process in June.

“I don’t think it’s where we would like it to finally end, as far as every specific thing in there,” Stayskal told Coffee or Die, “but it’s a phenomenal start. Prior to this passing, there was nothing. It’s not a perfect solution, but it’s far better than it was.”

A service member or a surviving family member must submit a written claim to specific places depending on the service branch, typically to the judge advocate for their branch or the judge advocate at the medical center at which the malpractice occurred.

The rule states that expert opinions are not required, and the claimant does not necessarily need an attorney. But claimants “have the burden to substantiate their claims,” according to the DOD, and should therefore submit as much supporting evidence as they can provide.

The malpractice in question must have occurred in a Department of Defense medical center, inpatient hospital, or ambulatory care center, by a covered DOD health care provider, such as a member of the uniformed services, DOD civilian employee, or personal services contractor. Claims must be filed within two years of the malpractice in question. This was extended to three years for claims filed in 2020 for events in 2017, but this extension has now lapsed.

Notably, for claims in which the Department of Defense determines malpractice occurs, any damages will be offset by payments from other programs, such as service members group life insurance, the death gratuity, the survivor benefit plan, and VA disability compensation. This could reduce the payments that claimants receive dramatically. Out of the approximately 50 claims filed, the DOD estimates only seven claims per year will require supplemental damages payments.

Payments up to $100,000 will be distributed directly from the Department of Defense, whereas larger payments will come from the Department of the Treasury. Settlements are final and conclusive, without any form of judicial review after the claims are adjudicated.

Critics of the new rule point out that the exact mechanism for determination is vague. The rule states the Department of Defense will follow the same standards as the Federal Tort Claims Act used in civilian medical malpractice cases, but it is unclear exactly who will be making the decisions and how.

“The entire review process is enshrouded in darkness,” advocate Dwight Stirling of the Center for Law and Military Policy told Navy Times.

“It’s kind of hard to point out something you don’t know the true answer to yet,” Stayskal said. “So we’re trying to give it the benefit of the doubt for now.”

The rule goes into effect July 19, and public comments will be received on the Federal Register website until Aug. 16.

Deverris Stuckey says his oldest two children are deeply scarred by their mother’s death. “My son, I think his mind hasn’t wrapped around the fact that she isn’t here anymore,” he said. “Four years later, he’s still wearing the same clothes that she purchased for him, even though they are way too small.”

Money will never reverse the tragedy his family has experienced.

“Don’t get me wrong, I love the military,” Deverris said. “The military gave me my start, the military made me a man, the military gave me an education. I’m not trying to say the military is the Big Bad Wolf. But the military is about accountability. If I work on an aircraft, and I put in the wrong part or I don’t install something, and the pilot goes to eject from the plane and can’t, my name is signed off on it. They will come back and look at those records, and, guess what, I’m going to be held accountable.”

Like so many other service members and their families, Deverris is hopeful that the Stayskal Act will finally hold the military accountable for their mistakes. “We served our country honorably and faithfully,” he said. “We believed in the system. We believed they were going to fix her.”

Call Now- Open 24/7

Call Now- Open 24/7